This week the city has been devoted to commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall exactly 30 years ago. Every time there is a big milestone like this, Berlin is packed with events and celebrations and people go a bit nuts for it. For the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, the city erected a line of eerie glowing white orbs along the entirety of the length of the wall from east to west. Every so often, as you travelled around the place, you would catch a glimpse of a stretch of this illuminated barrier; simply being there, not trying to say or mean anything explicity, but just shining peacefully in the blue darkness of the evening. The light of the orbs cast a whole new look into the most familiar corners of the city, and small mirrors hung from the trees sparkled and made the leafy parts feel like little pockets of magic.

On the last night of the celebrations, the orbs were to be let up into the sky like balloons. Duly we all gathered to watch, and there was a countdown, and then the countdown reached zero – and all the lights went off. The orbs became dark, dead plastic. They did then did indeed start levitating into the air but it was almost impossible to tell because it was the dead of night and THEY HAD TURNED OFF ALL THE LIGHTS. Thousands of people came out to stare into the night sky and imagine dozens of plastic balls floating up into the void. Just think how majestic it would have been to see a staggered sequence of thousands of glowing balloons rising to meet the darkness. But no; no one had thought that far ahead, and so we got what we got. Somehow, no one was surprised.

This year, as the 30th anniversary, something equally spectacular had to happen. And sure, there was a huge concert at the Brandenburg Gate and several open-air exhibitions around the city and some kind of shapeless crush of swarming human beings at Alexanderplatz, but everyone was talking about the big installation. See, the road behind the Brandenburg Gate is a huge, straight passageway that creates an astonishing visual funnel directing every glance right towards the golden fleck of the Victory Tower at its other end. To celebrate this momentous day, the city of Berlin had commissioned an artist to create a huge art installation along the length of this road, and it was to be dramatic and hopeful and awe-inspiring.

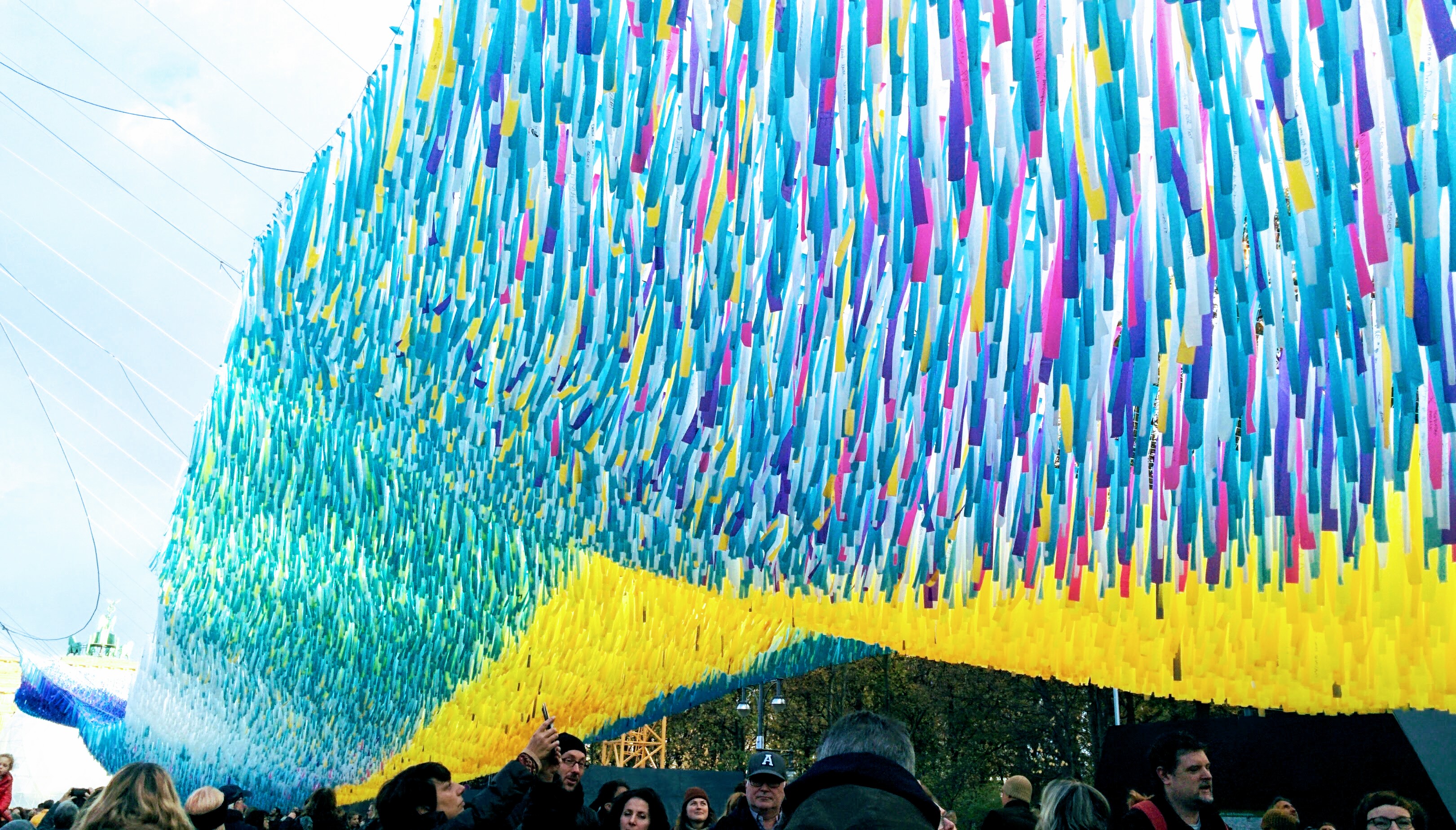

This artist, Patrick Shearn, has come up with something I’m sure he thinks is absolute genius: an enormous net, adorned with hundreds of thousands of strips of neon-coloured ripstop nylon, strung up over the Straße der 17. Juni so that the strips flutter and tickle in the breeze like the underbelly of a vast piñata. Each strip has a message of hope on it, written by people in the city, who were approached in various settings and asked to think about the future and other inspirational things. And the PR photos look fabulous; from a drone’s-eye view it truly is breathtaking, an endless-seeming kinetic ribbon of movement and light, striped in turquoise, purple and yellow.

So of course as a Berlin resident you simply have to go and see it. And so you make the journey over to the Gate, and you grit your teeth through the barely-moving trickle of people, and then suddenly you are there under this thing. And, well… it looks like bits of nylon sowed onto a bit of fishing net.

So, listen, issue number 1 here has got to be the actual construction of the thing. I don’t want to be a buzzkill; not all human endeavour can or has to be eco-friendly, and certainly you could argue that art in particular fulfils its own very important role in making the world a better place. But the last time I stood in the Straße der 17. Juni, it was for the world’s biggest and most vital ever environmental protest. And now we’re just gonna spend heaps of resources getting a bunch of plastic fabric, rendering it completely non-reusable by chopping it up and writing on it, and then sewing it to a plastic net and hang it up in triumph over that exact same space? This leads me, therefore, to my first piece of feedback for the organisers of this installation:

If the work is supposed to make us think about hope for the future, have the work reflect hope for the future.

Wouldn’t it have been so much better to create something sustainable, recyclable and organic, to show that any kind of historic celebration is also an opportunity to work harder and reject complacency? Anniversaries are not just about commemorating the achievements and liberations we have already won; they are also about showing that time and mankind continue to move forward, and we can never stop thinking about the future and our place in it.

Issue number 2 with this installation is the half-assedness of the whole endeavour. I mean, it’s nice walking along seeing the pretty colours, but then all of a sudden this vibrant curtain of trash just…stops. It only stretches about halfway along the road and then it’s over, and since the road is closed all that lies behind it is a sad empty space begging for some tumbleweed and an old vagrant playing the banjo. And on either side of the vivid, nudibranch-looking canopy are rows of enormous, sinfully ugly pillars of scaffolding, wrapped in clumpy feet of khaki-coloured plywood – presumably as an attempt to hide the unsightly frames, although this seems a little bit like trying to hide having a big nose by wearing an extremely gaudy pair of sunglasses.

Look at them; it’s like Mardi Gras in a world populated by JCBs. Foto: Paul Zinken/dpa +++ dpa-Bildfunk +++

Furthermore, as you wander along the length of the ‘art’, you begin to notice that there are only ‘messages of hope’ inscribed on a few of the scraps, but that most of them are blank. In fact, 70% of them are blank (I looked it up). What is the POINT of doing the gimmick with the messages if you’re not going to bother doing it with more than just a tiny portion of the installation? And then your eyes focus a tad more and you notice that the few inscribed strips don’t always contain messages of hope at all; loads of people have simply written their name – “Steffi <3 <3 ” – and left it at that. So we’re just gluing strips of bathroom stall graffiti to a fishnet now? Who project managed this? Time for more feedback.

If you’re going to make a massive installation which is supposed to capture the attention and imagination of an entire city, it needs to feel transcendental and perfect.

Don’t try to kid us that you didn’t have the budget. It costs no money to ask people to write things on bits of fabric with Sharpie; or you could have abandoned the Sharpie idea and used that bit of the funding to make the trash curtain longer. And sure, it must be tricky to figure out a way to hang up this big awning the way you want it, but there must be a more elegant way than with clodhopping chunks of yellow scaffolding every two metres. It’s a fishnet for cryin’ out loud – it can’t weigh that much.

And yet what bothers me most about this installation is something else. What still eats at me hours later is how uninspiring the concept is – a concept aiming, at its core, to inspire. But haven’t we all seen this before? The big eyecatching space, filled with tiny things (little cards, post-its, stickers, paper planes) that the public have embellished with their hopes, wishes and thoughts. Of course we have seen this before; it is the standard “and now some food for thought” part of every museum visit nowadays. The Jewish museum has a full-sized tree where people hang paper apples with their hopes for the future written on it; the Bodyworlds museum has a wall where you can stick stickers with your thoughts about the future of the human body; the Medizinhistorisches Museum has a wall where you can vote for your preferred interpretation of the nature of human mortality. I cannot count the number of times I have seen this inane bullshit – and it is bullshit, because it claims to mean everything and actually means nothing at all.

How does it bring us any insight to see this? Is it the idea of the sheer mass of hope, the scale of hundreds of people expressing their dreams and aspirations for the future? Because this is surely an extremely unexciting fact; millions of people have hopes and wishes, big whoop. Millions of people also get bored, and get excited to receive a letter, and occasionally crave a hot chocolate. Or is it the moment of connection created when you read someone else’s message? A message that was scribbled with little interest or concern because some Event Organiser asked them to? Is that poignant? To the people scrawling on the neon scraps, it doesn’t seem to have been poignant enough to write anything more insightful than one’s own name. Is that what we can call a “coming together”?

Pictured: people actually coming together. Conversing, making new friends, engaging in a shared dream. Also, everybody loves bubbles.

Collecting ‘messages of hope’ has become a lazy shorthand for representing actual hope, ambition and self-betterment. You can stand in front of your collection of hand-written messages and, with a proud sweep of your hand, inform people of how inspired they should be feeling right now when observing your installation – but like a bowl of cereal, the spectator doesn’t pause to appreciate the flavour of each individual flake and grain, they merely woof down the whole bowl without much thought. This is not a fault of the spectator; we are simply too dispassionate to be moved to fascination by a collection of schmalzy catchphrases.

In essence, this installation exemplifies what so many memorials and monuments do: they provide a repository for us to dump our guilt and our sadness and our wishes and our hope at the foot of a column along with a bunch of flowers, so we can go home and no longer think about it. Monuments are so often not a way to remember the dead, but rather to forget them by purging them into a solid shape and then considering that a job well done. This is the genius of the ‘Stolpersteine’ or ‘Stumbling Stones’ in Berlin: these little brass tiles, embedded seemingly at random from time to time in the pavement, simply have the names of individuals who were killed under the Nazi regime and the context in which they died. They are called ‘Stumbling Stones’ because you are meant to stumble upon them, discovering one or two by accident each day as you wander through the city. You can never really forget these lost people because they are always there, popping out at you, a part of the cityscape. Incidentally, people polish these stones and pay their respects at them on Kristallnacht – which also happened to be this weekend.

So sure, let’s write down all our hopes and wishes for the future and glue them to a big thing and then shove it somewhere and pretend like we’ve done something for the future. But, in fact, we have done nothing optimistic or meaningful; we have just put our bunch of flowers by the memorial column. Times are tough right now; we’re staring down the barrel of so many different crises, and we need hope to keep going. But the sight of thousands of people marching the streets for the climate was infinitely more hopeful. We need art that captures the dynamism and the action of the moment, that appreciates the freedoms we have won and acknowledges that we have so many more peaks to climb. So please, Patrick Shearn, accept my final bit of feedback:

Give us art that makes us think; not art that helps us not to think.